| ||||||

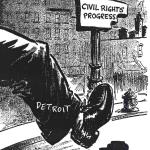

With the war drums of Birmingham, Alabama still resonating through the conscience of America, fate would now shift Detroit into the national spotlight. On this

one-hundredth anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation, the country again found itself embroiled in a civil war. For years there had been an undeclared civil war in the Deep South. No, this was not Shiloh or Vicksburg revisited but Albany, Little Rock, Montgomery, Birmingham and scores of other towns where victims of racial prejudice became faceless martyrs of a contrived system of justice.

Now the southern heat would hover over Detroit as the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. arrived on June 23rd, 1963 to lead a massive protest rally down heralded Woodward Avenue to bring attention to the plight of black southerners and racial injustice everywhere. It would be called the March for Freedom and Detroit’s tarnished image would receive a much needed shot of esteem.

There was another anniversary to be observed in Detroit on this hot summer day, albeit a shameful one. It was (not coincidentally) the 20th anniversary of the ‘43 riot which put Detroit in a spotlight of disgrace around the world. Local Reverend C.L. Franklin, the man who organized the march, felt that the ‘43 riot was a point of reference: “The same basic, underlying causes for the disturbance are still present. The difference now will be the way our protests and dissatisfaction will be made known.”

King, whose base of operations was centered in the South, began testing northern waters for racial intolerance. What better place to start than Detroit, which had a notorious past but, under new Mayor Jerome Cavanagh, an encouraging future.

MLK’s Six Principles of Nonviolence

1) Nonviolence is a way of life for courageous people.

Nonviolence is a way of life for courageous people.

2) Nonviolence seeks to win friendship and understanding.

Nonviolence seeks to win friendship and understanding.

3) Nonviolence seeks to defeat injustice not people.

Nonviolence seeks to defeat injustice not people.

4) Nonviolence holds that suffering can educate and transform.

Nonviolence holds that suffering can educate and transform.

5) Nonviolence chooses love instead of hate.

Nonviolence chooses love instead of hate.

6) Nonviolence believes that the universe is on the side of justice.

Nonviolence believes that the universe is on the side of justice.

"I told my child about the color bar after

she begged to be taken to Fun Town, an Atlanta

amusement park that she’d seen advertised on

television. I knew they did not admit Negroes.

But I told her that, even though she could not go,

she was as good as anybody else. It isn’t easy to

explain such things to a seven-year-old."

“Detroit will never be the same after this day”

Detroit, Michigan, the scene of the infamous 1943 race riot which cauterized the city as a

malfunctioning melting pot that boiled over in front of the world, embarrassing the city and country and exposing a hidden vein of hatred that was coursing through the greatest industrial city in the world. The city was a Frankenstein's monster of warring factions from all parts of the country with only the commonality of hatred linking them together.

Twenty years later Detroit was re-tooling like the sleek Cadillacs it was cranking out. The new power plant was Mayor Jerome Cavanagh, a young, liberal progressive bent on distancing the city from it's insurrectional past. Cavanagh quickly gained traction, propelling the city past old barriers and into uncharted visions based on civil liberties and not civil war.

With the specter of Birmingham, Alabama still resonating through the conscience of America, fate would now shift Detroit into the national spotlight. On this one-hundredth anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation, the country again found itself embroiled in a civil war. For years there had been an undeclared civil war in the Deep South. No, this was not Shiloh or Vicksburg revisited but Albany, Little Rock, Montgomery, Birmingham and scores of other towns where victims of racial prejudice became faceless martyrs of a contrived system of justice.

Now the southern heat would hover over Detroit as the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. arrived on June 23rd, 1963 to lead a massive protest rally down heralded Woodward Avenue to bring attention to the plight of black southerners and racial injustice everywhere. It would be called the March for Freedom and Detroit’s tarnished image would receive a much needed shot of esteem.

There was another anniversary to be observed in Detroit on this hot summer day, albeit a shameful one. It was (not coincidentally) the 20th anniversary of the ‘43 riot which put Detroit in a spotlight of disgrace around the world. Local Reverend C.L. Franklin, the man who organized the march, felt that the ‘43 riot was a point of reference: “The same basic, underlying causes for the 1943 disturbance are still present. The difference now will be the way our protests and dissatisfaction will be made known.”

King, whose base of operations was centered in the South, began testing northern waters for racial intolerance. What better place to start than Detroit, which had a notorious past but, under Cavanagh, an encouraging future.

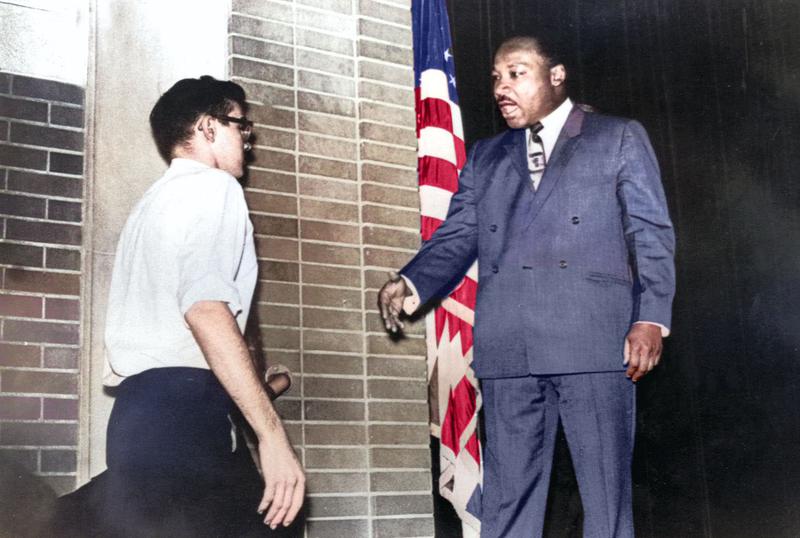

March of 1968 - Martin Luther King, in his last appearance in Michigan, greets a student at Grosse Pointe High School. In three weeks he would be dead of an assassins bullet and the Civil Rights Movement, long since sputtering because of the riots, would come to a screeching halt. Kings legacy would live on in his words:

If you can’t be a highway, just be a trail

“He is known as the good Samaritan. Jesus says in substance that this is a great man. He was great because he could project the “I” into the “thou.”

On November 22nd, 1963 found Dr. King at home doing work in his study. With the television on in the next room, King seemed to notice a commotion and investigated. It was Walter Cronkite announcing that President Kennedy had been assassinated. King, beside himself with grief for his friend, announced to his wife who was standing over him, "Cori, this is what's going to happen to me also. I keep telling you, this is a sick society.''

MLK's Cobo Hall speech in its entirerty.

March to Freedom

June 20, 1963 Detroit, Mich

The sun rose brilliantly over Detroit in tandem with an oven like heat, much like it had twenty years before to start the most infamous day in the city's history. But this is now 1963, not 1943, and today's agenda called for conciliation, not conflagration. With the advent of the historic March to Freedom on the anniversary of the infamous 1943 riot, Detroit's shady reputation would go from shame to fame in an afternoon.

The year 1963 would be the high water mark for the civil rights movement. Detroit’s March to Freedom was sandwiched in between two historic events. Two months after the fire hoses of Birmingham and two months before the camaraderie of King’s celebrated March on Washington. The march was originally planned as an expression of sympathy for marchers in Birmingham but later took on the cause of ending discrimination.

Downtown merchants along the march route, perhaps playing back memories of the 1943 riot, closed their stores fearing the worst. Detroit Police Commissioner George Edwards went to great lengths to assure a peaceful demonstration. Edwards army that descended on Woodward Avenue that day consisted of a district inspector, 2 precinct inspectors, 8 Lieutenants, 28 Sergeants (25 of them Black), 23 detectives and 452 patrolmen. Edwards reassured King: “You’ll see no dogs or fire hoses here.”

The starting area was at Woodward and Adelaide at 3 p.m. When King arrived, heavily escorted by police, the crowd surged towards him hoping for a handshake. The crowd was estimated at conservative 125,000 although some believed it to be much higher. It exceeded even the most optimistic expectations. There were only four arrests and no incidents. An ebullient King, stunned at the magnitude and enthusiasm on display in Detroit, commented that the March to Freedom was “the greatest civil rights demonstration ever held in the United States. I’ve faced so many mobs of hate in the South, this was kind of a relief."

The march took on the appearance of an Easter Parade as entire families pushing strollers walked with arms linked in a symbol of solidarity. The crowd, which was primarily black, was an eclectic mix of race, age, gender. Many brought lawn chairs simply to watch from the sidewalk but were often spurred on by the marches to join in, “You ain’t in Mississippi. You don’t have to be afraid. Let’s walk.”

“I am ashamed I live in Dearborn”

“We Want Freedom Now”

“Evers died for You – Join the NAACP for Him”

(civil rights leader Medger Evers was gunned down only 16 days prior to the march)

At the end of the march, spectators rapidly filled Cobo Arena and then overflowed into the adjacent Cobo Hall. Thousands more stayed outside and listened on loud speakers. King was introduced to the enthusiastic crowd by Michigan Congressmen Charles Diggs, which resulted in a minutes long standing ovation. Using Detroit as a sounding board, it was here that King first gave his "I Have a Dream" speech to a sizable crowd (the first time was in front of a high school audience at Rocky Mount).