Economy Printing - The Raid

Bill Scott always took an active part in the 12th Street community. The trouble was, people being what they are, no one else seemed too interested in dabbling in community politics. But Bill Scott knew that the world was changing, and with the civil rights movement in full force, the political stars would never

be aligned this way again. Unable to spark his neighbors into action, he put his keen street instincts

to work and conjured up a drawing card, the United Community League for Civic Action.

It was formed in 1964 for the express purpose of backing local political candidates running for office and thus helping the neighborhood gain some badly needed political clout. To house his ambitions, Scott leased the upper floor of the vacant Economy Printing building in 1966 just north of Clairmount on 12th Street.

Bill Scott II

"They Call Me Bill"

Politicians often helped pay the expenses of the United Community League because they knew Scott could get the word out. In off-election years the contributions, not surprisingly, slowed to a trickle. Nevertheless, Economy Printing was considered an ideal location in the heart of a burgeoning black populace. Scott had been told, “to hold onto this good location when political activity was slow, even if it meant running a speakeasy.” On the weekends, this is exactly what Scott would do. It was a chance for the locals to blow off steam, gamble, have some soul food and, of course, drink. For Scott, it was a chance to indoctrinate patrons into the political process.

Since they had no liquor license, gambling license or permission to host such sordid activities, police departments are compelled to shut them down. The catch is that the illegal acts must be witnessed, and blind pig operators generally possess a real faculty for keeping this from happening.

Take Bill Scott’s humble abode off 12th Street. Housed on the second floor of the defunct Economy Printing, it was impossible to observe illegal activity despite the obvious debauchery that could be heard from the street. Economy Printing had been raided numerous times over the years. Only a three-wood away from the elite Boston-Edison sub division, the late night revelry was a constant source of irritation for upper-class locals.

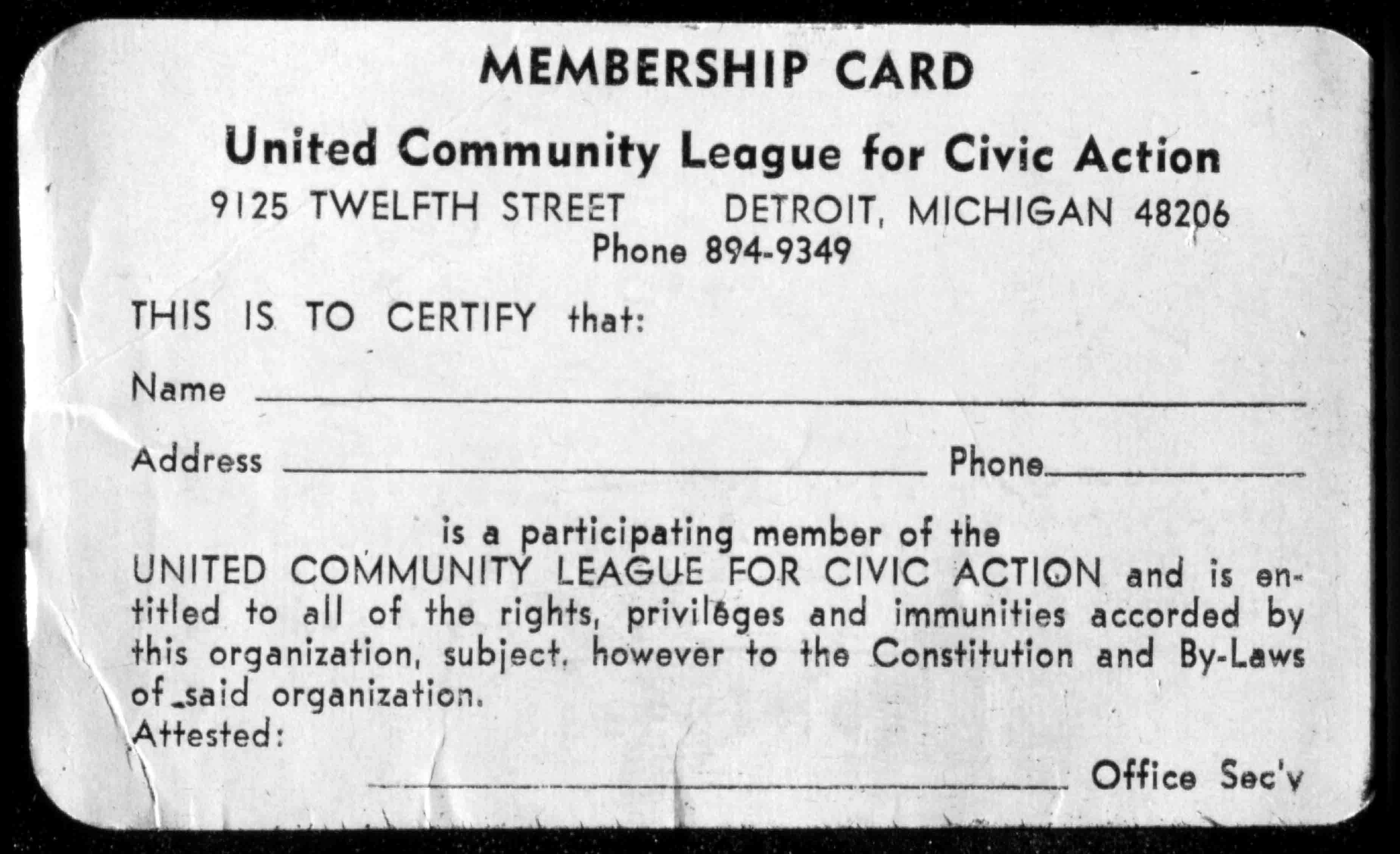

The membership card for Bill Scott’s United Community League. To gain admittance to the blind pig, you knocked on the front door and the peephole opened. You either flashed the card or provided a password. If the doorman was the least bit suspicious, the peephole slammed shut and you went elsewhere.

"This guy just wouldn't give up!"

At 3:30 Sunday morning, July 23rd, Bill Scott was hosting a party for two black servicemen who just came back

from Vietnam and another who was on his way over. Detroit Police had tried to "tip" Bill Scott's party on nine other occasions but were successful only twice. On Feb 11, 1966 they raided Economy Printing at 3:00 a.m. and were successful in netting ten party goers. On June 3, 1967 another raid was conducted at 2:30 a.m., this time netting twenty-eight people.

Seven weeks later, Detroit was in the middle of a heat wave. Unbeknown to Bill Scott, undercover Detroit police officer Charles Henry was walking through his front door in an attempt to bust him and his operation. Henry later testified he bought a beer from Scott for 50 cents. Scott claimed it was on the house. A few minutes later, Henry's superior, Sgt. Arthur Howison, came crashing through the front door with his men in tow. Howison was stunned to find not the usual 15 or 20 party goers but 83! Multiple paddy wagons would have to be summoned to cart all these people to the 10th Precinct. This would take time. On 12th Street, which was well known for its 24 hour pedestrian party goers, this would spell doom for the DPD.

For the next hour, Howison & co would count the agonizing minutes awaiting for the arrival of the next paddy wagon. By 4:30 a.m., Detroit police were beginning to get concerned. Sgt. Smith (upstairs) was informed by a patrolmen downstairs loading the paddy wagons that “It’s getting a little hairy outside. Hurry up!” What had initially been 30 bystanders when the first paddy wagon was loaded had now swollen considerably.

Now some 200 protesters began to throw bottles and bricks against the building and the cat calls were getting ever louder, but one voice seemed to stick out. “One of the first people I noticed as being the ring leader, said Sgt. Smith, and the most harassing one out there was the one we later dubbed Green Sleeves and he was staying well back into the crowd. When I first observed Green Sleeves he was standing on the east side of 12th Street by the curb.”

Dubbed “Green Sleeves” by Detroit police because, despite the sweltering weather, he was wearing a long sleeve green shirt and bright green pants. While Detroit police conceded that it wasn’t unusual to get cat calls from the crowd during a raid, “we never had one or two outstanding people like this one (Green Sleeves, the other was Bill Scott III, son of the Blind Pig proprietor), the majority of the time it’s spotty, it comes from everywhere but this guy (Green Sleeves) just wouldn’t give up.”

Michael Lewis, the ill-famed “Green Sleeves,” was the man accused of inciting the crowd outside Economy Printing and starting the riot. At the time he was known to the police in attendance only as Green Sleeves because, despite the sweltering temperature he wore a long green-sleeved shirt. With his constant, belligerent diatribes launched at the patrolmen tending the paddy wagons on 12th Street, he was able to turn the jovial crowd into a tempestuous mob.

While the police deny any charge of brutality, decades of aberrant behavior needed only a fuse. The raid itself was poorly executed, taking an hour in a neighborhood known to be seething with anti-police sentiment. Even hours after the raid Lewis was seen by police directing the rioters and continuing to foment rage.

Michael Lewis

The notorious "Green Sleeves"

Lt. Raymond Good, in charge of the night shift at the 10th (Livernois) Precinct, took a cruiser to the scene and described what he saw: “We pulled up to the corner (12th & Clairmount) A large crowd - maybe 200 or 250 people - was milling around on the southeast corner. They were watching and yelling things at out precinct cleanup crew, which was herding people out of Economy Printing and into a Paddy wagon to take them to the station. It was a hot, muggy night. It wasn’t unusual to have large numbers of people awake and even walking the streets in that area because of the heat. While the crowd was loud, they didn’t look very mean. A few wastebaskets and other debris littered the street. Then a tall, thin young man in a green shirt (latter we tagged him Mr. Green Sleeves) came out of the crowd and started yelling, “Get the cops off the streets. Let’s get them whiteys. Don’t let them take these people away. We’re going to start a riot. You’re going to get yours. The streets are ours.” He kept yelling and the crowd responded with catcalls. Greensleeves walked across Clairmount in front of our car. I opened the right door and put one foot on the street to see him better as he moved toward the crowd, screaming and waving his arms. Then I saw stars. Someone behind me had thrown a piece of concrete and hit me above the right ear.

I got back in the car and told the driver to 'get the hell out of here.'”

Mr. Green Sleeves remained unidentified until about two weeks after the riot. Later arrested and identified by Lt. Good as Michael Lewis, a Ford Motor Co employee, he was charged with inciting a riot and two counts of looting. Lewis' first trial ended in a hung jury. He was later acquitted of the charges.

Looking back at the early hours of the riot, Lt. Good believes the immediate cause was the exhortation of the crowd by Mr. Green Sleeves at 12th and Clairmount. “If he hadn’t been there urging them on, probably the crowd would have broken up and gone home.” According to Police Commissioner Ray Girardin, it was probably a mute point, “We all thought we would have a riot this summer because there were just too many Green Sleeves on the streets for a chance to turn something.”

Economy Printing was well known to the Clean Up Squad at the Tenth Precinct. Nine attempts had been made to raid the after hours soiree at 9125 Twelfth Street in the 16 months before the riot. On February 11, 1966 at 3:00 a.m., the Tenth Precinct arrested ten persons. On June 3, 1967, at 2:30 a.m., the Clean Up Squad raided Economy Printing and arrested some 28 partiers. Only seven weeks later the fatal raid was conducted.