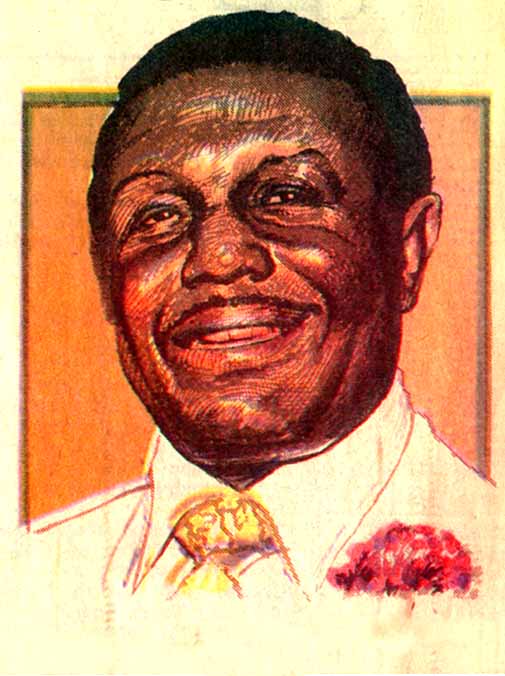

Born in Sunflower County, Mississippi in 1915, Clarence Laverne Franklin grew up experiencing firsthand the hatred of the Jim Crow South. But the lessons of hatred were not to embitter him: rather than hate back he sought to extinguish these flames by preaching the gospel. It turned out to be an incredible journey for him and for all those who met up with him along the way. ranklin came to Detroit in 1946 to become pastor of the New Bethel Baptist Church which in those days was on the the East side on the corner of Hastings and Willis in Black Bottom. Finally settling on Detroit’s West Side, he would become Detroit's most legendary preacher who for decades lectured his congregation on the necessities of fortitude and forgiveness.

He knew at the age of fourteen that he wanted to be a preacher and make a difference. The sharecropping life, with its endless weary hours of backbreaking work, was not for him. Franklin knew well the bitter hand of discrimination. Mississippi was the bastion of Jim Crow, removed from slavery in name only. “I knew segregation in the raw,” Franklin recalled. “I vividly remember walking to school and being passed by a bus full of white kids, who shouted such abuses as “nigger” and “coon” at me from the windows. I feel very fortunate in having those experiences because I learned a great deal.” Instead of reciprocating this hatred, he channeled his energy into learning and preaching the gospel, a skill at which he soon became formidable.

Franklin was a circuit preacher in Mississippi. Owing to the ruralness of the area, he preached at a different church each Sunday. Franklin quickly found himself the pastor of four churches at the same time. He would travel by Model T or horse-drawn wagon, whatever it took to get the word out.

There was an old man in Mississippi who pastored in a rural community. This minister passed on a few years ago. In his Sunday night services he used to say:

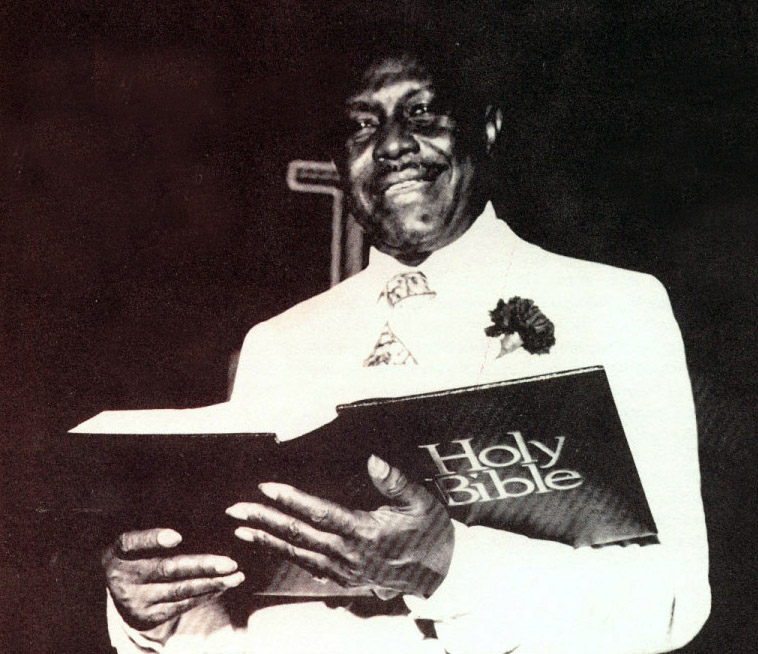

Reverend C. L. Franklin - Motor City Moses

| ||||||

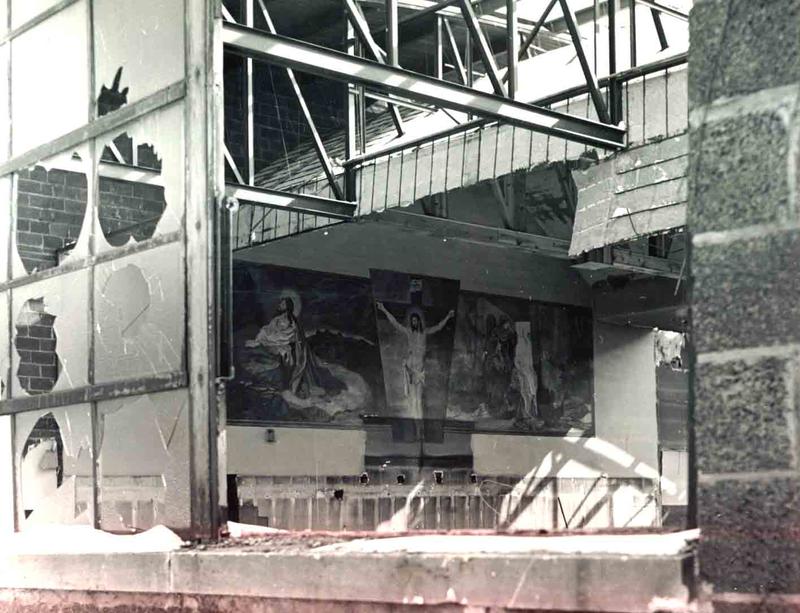

Like many black Detroiters, Reverend Franklin would feel the sickening sting of urban renewal. After painstakingly putting down roots in Detroit's Black Bottom, the city would clamp eminent domain on Franklin's New Bethel Baptist Church, citing it stood in the way of progress. New Bethel would soon fall to the wrecking ball, forcing Franklin and many of his parishioners into their own personal Genesis.

Showing his typical resilience, Reverend Franklin would recover from the debacle of urban renewal and re-establish himself on Detroit West Side. After a brief stint on 12th Street, his New Bethel Church wound up on Linwood Avenue.

In an effort to reach greater audiences, Reverend Franklin began recording his sermons on albums which sold in the millions. As a result he was known as “The Pastor of Millions.” For some thirty years, his familiar voice could be heard Sunday evenings preaching the gospel on radio. Franklin was one of the old school, fire and thunder but enlightening preachers whom the community centered around and sought out for leadership.

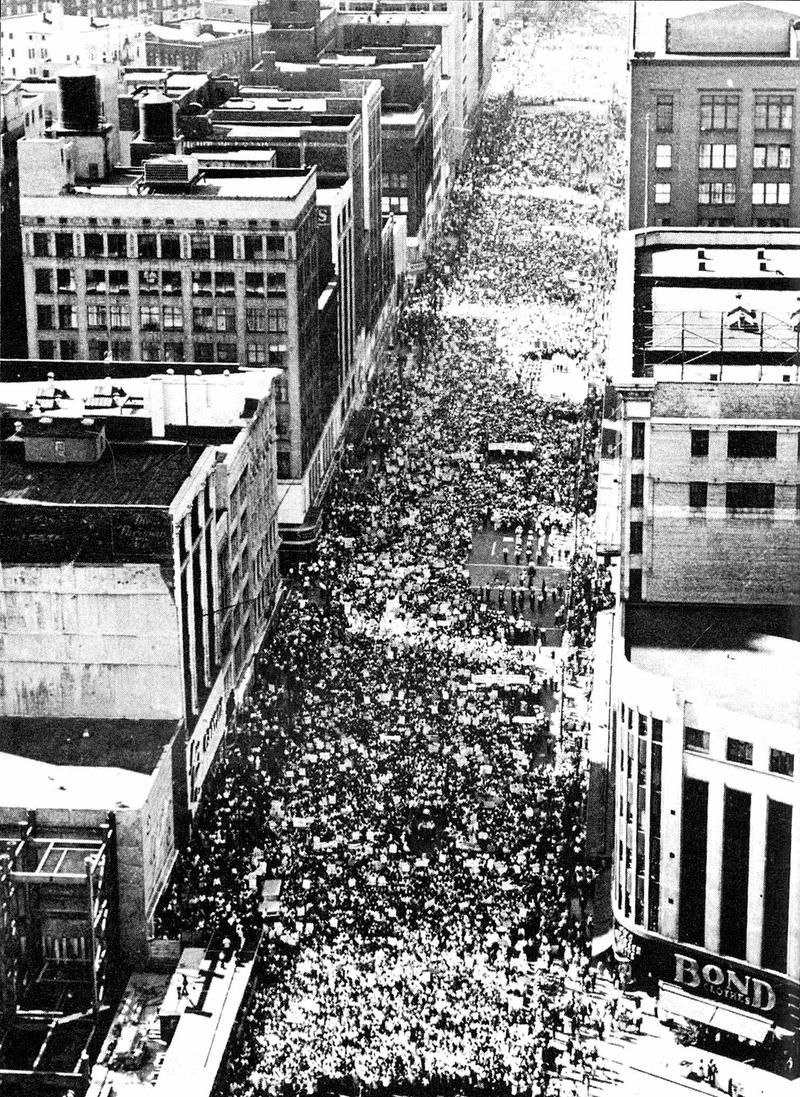

An outspoken advocate of civil rights, he eventually crossed paths with Martin Luther King and the two hit it off fabulously, becoming close friends. It was the Reverend Franklin who proposed and organized the famous March for Freedom down Woodward Avenue which helped solidify Detroit’s image as a Model city.

King and Franklin, titans of civil rights, would team up in 1963 and create the most historic day in Detroit history only eleven days after the assassination of civil rights

trailblazer Medgar Evers. Knowing Detroit's violent past King found himself once again trusting in providence and praying for peace.

The 1963 March for Freedom - Detroit

King would use this event as a sounding board for his memorable "I have a dream" speech which he would give in Detroit two months before his march on Washington.

The march was seen as a standard of civility for civil rights marches. Under the Cavanagh administration Detroit would become known as the Model City because of their commitment to advance civil rights and negate aberrant behavior towards minorities. Detroit would be one of the few northern cities that embraced King: “I’ve faced so many mobs of hate in the South, this was kind of a relief.” Subsequent visits to other northern cities reconfirmed King’s suspicions that the hate was nationwide.

Detroit's historic March for Freedom occurred on June 20th, 1963, exactly twenty years to the day of Detroit's notorious 1943 riot, a tragedy that exposed Detroit to the world as a barbaric bees nest of hatred. "The same underlying causes for the riot are still present today," said Franklin. "The difference now will be the way our protests and dissatisfaction will be made known." In 1963, King and Franklin would set things straight. In the space of an afternoon, Detroit catapulted from worst to first in race relations and proved that Detroit stood for something other than automobiles.

(Below) - King, with Franklin on his left, leading the march.

The March for Freedom was originally intended as a show of support for those in Birmingham where an ominous cloud still hovered over the beleaguered city. But blacks from all walks of life were now for the first time stepping up en masse to voice their disapproval about latent civil rights progress. Again King would offer a fortuitous hint in regards to the impending race riots:

“The shape of the world does not afford us the luxury of an anemic democracy.

King, now thirty-four, found himself at the apex of his career. His keen political calculus enabled him to stage the coup of Birmingham that had an unparalleled influence on a previously unsympathetic white community. But King found, much to his dismay, that as he traveled to various northern cities there was often resentment from local civil rights leaders that he was interfering. In actuality, mayors and city council members simply had no confidence in many local leaders and hoped King’s great presence could soothe the choppy waves.

On this brilliant 23rd day of June, throngs of people filled Woodward from sidewalk to sidewalk, anxiously awaiting the arrival of their civil rights champion. The King entourage, which had flown in from Washington after a conference with President Kennedy, had arrived late. The parade was delayed, with great difficulty, until King could be transported. As Cavanagh waited at Woodward and Adelaide, a car pulled up. As King got out, the crowd surged towards him: “There he is!” everyone shouted.

As police officials escorted King over to an anxious Mayor Cavanagh to begin the march, Cavanagh at once linked arms with King and yelled as the masses surged towards them, “Hang on!” They tried to talk en route to Cobo Hall but the din of the crowd made it nearly impossible.

Hundreds of curious onlookers lined the sidewalks as the march progressed down Woodward, their idleness singling them out. One marcher waved them over, “Come on, get out here. You ain’t in Mississippi. You don’t have to be afraid here.”

As two of the many fascinated spectators continued to watch the endless sea of marchers pass by, one said in bewilderment, “You know, Detroit will never be the same after this day.”