Police Departments are always under the public microscope. Their actions must always be correct or they invite public rebuke. According to Arthur Niederhoffer, a twenty-year New York City police officer and a sociology professor at New York’s City College:

"No policeman enforces all the laws of a community. If he did, we would all be in jail

before the end of the first day. The laws which are selected for enforcement are those which the power structure of the community wants enforced. The police official’s job

is dependent upon his having radar-like equipment to sense what is the power structure  and what it wants enforced as law. "

and what it wants enforced as law. "

The Detroit police department had enforced the laws of the power structure since its creation in 1866. With the rapid social changes of the 20th century, the power structure added halting black encroachment to their list. The DPD could not stem the tide indefinitely, however, and the social bomb that had built up for decades would all catch up to Detroit in 1967.

Louis Berg Sr.

Detroit Police Superintendent

1940-1944

Louis Berg Jr.

Detroit Police Superintendent

1958-1963

James Berg

Deputy Detroit Police Superintendent

1958-1963

A lone policemen leaves a final remembrance to his former boss.

The Berg brothers represented the Old Guard of the Detroit Police Department. Like their father before them, they were Old school. But the social upheaval of the 1960s in tandem with the juggernaut of the oncoming civil rights movement was causing all big city police departments to change against their will. Professor Niederhoffer concedes:

"From within the system, a conflict of values is spreading confusion. The old police

code symbolized by the “tough cop” is waning. The new ideology glorifying the

code symbolized by the “tough cop” is waning. The new ideology glorifying the

“social scientist police officer” is meeting unexpected resistance. The external

“social scientist police officer” is meeting unexpected resistance. The external

force of social change has set the police organization adrift in uncharted territory."

force of social change has set the police organization adrift in uncharted territory."

Integrity! That was the common descriptor for Louis Berg Sr., the man who led the Detroit Police Department through it darkest days. “Big Louis” was old school, a policeman’s policeman who not only went by the book, over the years he actually wrote the police department manual. The real-time experience that life’s hard knocks presented an invaluable lesson to him growing up: “A black eye now and then is an equalizing spice for any education.” The Berg family left an indelible mark on the Detroit Police Department, providing over fifty years of distinguished service and molding the department into one of the best crime fighting units in the country.

Big Louis was appointed superintendent after a massive scandal rocked the department. The tentacles of corruption even reached City Hall, sending Detroit Mayor Richard Reading to jail. Police Commissioner Frank Eamon went through the police department with a flame thrower, firing dozens of high-ranking commanders. Berg, who was one of the few found untainted by the graft, was asked to pick up the pieces. He was making swift work of it too until the ‘43 riot came along, causing yet another of life’s black eyes.

Big Louis was appointed superintendent after a massive scandal rocked the department. The tentacles of corruption even reached City Hall, sending Detroit Mayor Richard Reading to jail. Police Commissioner Frank Eamon went through the police department with a flame thrower, firing dozens of high-ranking commanders. Berg, who was one of the few found untainted by the graft, was asked to pick up the pieces. He was making swift work of it too until the ‘43 riot came along, causing yet another of life’s black eyes.

Street educations that police absorb offer the highest and lowest of emotional extremes that are difficult to parallel in civilian life. Perhaps that is what attracted Berg’s two sons, Louis (Little Louis) and James to the profession. The two boys would often accompany their father on weekends to the old Hunt Street Station where he was the district commander. Here they reveled in the atmosphere of good versus bad and right versus wrong, unleashing a torrent of curiosities against unsuspecting detectives who naively allowed themselves to be cornered. Big Louis, who never wanted his sons to become policemen, would then give his “pesky kids” a quarter and send them to the movies.

Street educations that police absorb offer the highest and lowest of emotional extremes that are difficult to parallel in civilian life. Perhaps that is what attracted Berg’s two sons, Louis (Little Louis) and James to the profession. The two boys would often accompany their father on weekends to the old Hunt Street Station where he was the district commander. Here they reveled in the atmosphere of good versus bad and right versus wrong, unleashing a torrent of curiosities against unsuspecting detectives who naively allowed themselves to be cornered. Big Louis, who never wanted his sons to become policemen, would then give his “pesky kids” a quarter and send them to the movies.

After thirty-three years of service, Berg Sr. would himself run philosophically afoul of a strong willed police commissioner. The new commissioner saw the police as a sociological extension of the community and had an extensive collection of graphs, charts and statistics to prove it. The old school Berg viewed the common criminal as a public enemy to society and not as a problem child. His refusal to budge on these principles that had been taught to him over three decades of police work ultimately forced him into retirement. They say lightning never strikes in the same place twice. Or does it?

After thirty-three years of service, Berg Sr. would himself run philosophically afoul of a strong willed police commissioner. The new commissioner saw the police as a sociological extension of the community and had an extensive collection of graphs, charts and statistics to prove it. The old school Berg viewed the common criminal as a public enemy to society and not as a problem child. His refusal to budge on these principles that had been taught to him over three decades of police work ultimately forced him into retirement. They say lightning never strikes in the same place twice. Or does it?

Despite the elder Berg’s protestations, the two boys did join the Detroit Police Department and began a meritorious rise through the ranks that would land them in their father’s old office at 1300 Beaubien, the first brother combination to have achieved that distinction. But the “old Detroit” that their father presided over was quickly slipping away. In its place was an ever changing mass of social confusion that constantly took on new dimensions.

Despite the elder Berg’s protestations, the two boys did join the Detroit Police Department and began a meritorious rise through the ranks that would land them in their father’s old office at 1300 Beaubien, the first brother combination to have achieved that distinction. But the “old Detroit” that their father presided over was quickly slipping away. In its place was an ever changing mass of social confusion that constantly took on new dimensions.

The Crusader

The apple doesn’t fall too far from the tree, as the saying goes. George Jr. shared his father’s socialist views and his thirst for justice. Inculcated at Southern Methodist University and Harvard, he found himself ill-suited for the rigid Ivy League aristocracy which seemed to saturate the stuffy Cambridge air.

Edwards was in charge of Detroit’s public housing during the Sojourner Truth crisis in 1942. He spearheaded the drive to keep Sojourner Truth a black housing project, a feat which won him much admiration in the black community. He latter became president of the Detroit Common Council, garnering more votes than any of his peers. Believing votes equated to popularity, he decided to run for mayor against Albert Cobo in 1949 and was soundly thrashed. For perhaps the first time in his life, Edwards was forced to question the reality of his convictions and ponder if society was capable of change.

Edwards was in charge of Detroit’s public housing during the Sojourner Truth crisis in 1942. He spearheaded the drive to keep Sojourner Truth a black housing project, a feat which won him much admiration in the black community. He latter became president of the Detroit Common Council, garnering more votes than any of his peers. Believing votes equated to popularity, he decided to run for mayor against Albert Cobo in 1949 and was soundly thrashed. For perhaps the first time in his life, Edwards was forced to question the reality of his convictions and ponder if society was capable of change.

Years later, as the newly elected Jerome Cavanagh began forming his cabinet in 1962, black Detroiters waited with baited breath for his critical choice of police commissioner. The Miriani crackdown had left the city on a jagged edge. Cavanagh would have to choose someone cut from a liberal cloth to demonstrate a different degree of professionalism. Ray Girardin, a Cavanagh confidant and loyal friend, suggested George Edwards, a ghost from Detroit’s past who had been pounding a gavel in Lansing as the war drums of Detroit reverberated past his chamber. With Cavanagh’s approval Girardin approached his old friend Edwards with the proposition. Edwards recoiled at the suggestion. “Ray, Supreme Court judges don’t resign to become police commissioners.” Out of respect for Girardin, however, Edwards agreed to meet with Cavanagh under the proviso that it was merely out of inquisitive curiosity.

Years later, as the newly elected Jerome Cavanagh began forming his cabinet in 1962, black Detroiters waited with baited breath for his critical choice of police commissioner. The Miriani crackdown had left the city on a jagged edge. Cavanagh would have to choose someone cut from a liberal cloth to demonstrate a different degree of professionalism. Ray Girardin, a Cavanagh confidant and loyal friend, suggested George Edwards, a ghost from Detroit’s past who had been pounding a gavel in Lansing as the war drums of Detroit reverberated past his chamber. With Cavanagh’s approval Girardin approached his old friend Edwards with the proposition. Edwards recoiled at the suggestion. “Ray, Supreme Court judges don’t resign to become police commissioners.” Out of respect for Girardin, however, Edwards agreed to meet with Cavanagh under the proviso that it was merely out of inquisitive curiosity.

Edwards was immediately taken with the brash young mayor. Perhaps it was because in Cavanagh he saw a younger version of himself. Although Edwards was fourteen years his senior, the similarities were uncanny. Both had run for mayor of Detroit while the city was on the cusp of violence. Both fought for the underdog and both ran on a liberal, civil rights oriented platform. Edwards was greatly impressed with the Cavanagh’s acute grasp of social and legal issues that still hovered menacingly over Detroit, issues the city had routinely chose to ignore in the past. While Edwards came away from the meeting without a hint of committal, his passion for the Motor City had been rekindled.

Edwards was immediately taken with the brash young mayor. Perhaps it was because in Cavanagh he saw a younger version of himself. Although Edwards was fourteen years his senior, the similarities were uncanny. Both had run for mayor of Detroit while the city was on the cusp of violence. Both fought for the underdog and both ran on a liberal, civil rights oriented platform. Edwards was greatly impressed with the Cavanagh’s acute grasp of social and legal issues that still hovered menacingly over Detroit, issues the city had routinely chose to ignore in the past. While Edwards came away from the meeting without a hint of committal, his passion for the Motor City had been rekindled.

Edwards agonized over the decision. In the end it was his spirit of altruism and the flashbacks to 1943 riot which made his decision for him. “If Detroit did blow up in another race riot like the one we had lived through in 1943, I knew I could not live with the knowledge that I had been offered a chance to stop it – and had refused to try.” Word of Edwards’s hiring sent a shudder through the Old Guard at 1300 Beaubien. Edwards’s long sojourn in Lansing had not dulled his memory of black and white relations. While the black community may have rejoiced at his selection as police commissioner, the white community bristled. His long-standing reputation as a liberal maverick was also sure to meet a cold reception from a police department used to practicing old-fashioned police methods.

Edwards agonized over the decision. In the end it was his spirit of altruism and the flashbacks to 1943 riot which made his decision for him. “If Detroit did blow up in another race riot like the one we had lived through in 1943, I knew I could not live with the knowledge that I had been offered a chance to stop it – and had refused to try.” Word of Edwards’s hiring sent a shudder through the Old Guard at 1300 Beaubien. Edwards’s long sojourn in Lansing had not dulled his memory of black and white relations. While the black community may have rejoiced at his selection as police commissioner, the white community bristled. His long-standing reputation as a liberal maverick was also sure to meet a cold reception from a police department used to practicing old-fashioned police methods.

Above all, George Edwards was a crusader. He did not resign as a Supreme Court judge to become a token figurehead of a police department, giving rosy idealist speeches to the Rotary Club or presiding over Eagle Scout ceremonies. All his life he had wanted to mold Detroit into his version of a social Arcadia. His stinging mayoral defeat in 1949 left an open wound that had never healed. Now he sought closure. Edwards would go nose to nose with his police department for the next two years. Who would blink first?

Above all, George Edwards was a crusader. He did not resign as a Supreme Court judge to become a token figurehead of a police department, giving rosy idealist speeches to the Rotary Club or presiding over Eagle Scout ceremonies. All his life he had wanted to mold Detroit into his version of a social Arcadia. His stinging mayoral defeat in 1949 left an open wound that had never healed. Now he sought closure. Edwards would go nose to nose with his police department for the next two years. Who would blink first?

George Edwards Jr. had all but given up on the city of Detroit after losing the mayoral election to Albert Cobo in 1949. He was too liberal even by Democratic standards. In 1956, when Governor “Soapy" Williams appointed Edwards to the Michigan Supreme Court, Edwards headed for Lansing and left Detroit behind for good, or so he thought.

Edwards pursued the world of jurisprudence because it afforded him the opportunity to impart his liberal socialist’s views. Edwards was born and raised a Texan, where he witnessed more than his share of racist incidents. Now a transplant to Michigan, he understood the southern black frustrations and their perpetual thirst for justice.

Edwards pursued the world of jurisprudence because it afforded him the opportunity to impart his liberal socialist’s views. Edwards was born and raised a Texan, where he witnessed more than his share of racist incidents. Now a transplant to Michigan, he understood the southern black frustrations and their perpetual thirst for justice.

Edward’s father, George Edwards Sr., was a John Brown type character. A radical lawyer, he was once kidnapped by the KKK at gun point only to be released while his black clients were beaten. Edwards quickly realized the outcome could easily been gruesomely different. His frequent defense of blacks throughout the Lone Star State continued to draw the ire of the KKK and only swift reflexes kept him one step ahead of their retribution.

Edward’s father, George Edwards Sr., was a John Brown type character. A radical lawyer, he was once kidnapped by the KKK at gun point only to be released while his black clients were beaten. Edwards quickly realized the outcome could easily been gruesomely different. His frequent defense of blacks throughout the Lone Star State continued to draw the ire of the KKK and only swift reflexes kept him one step ahead of their retribution.

George Edwards

Detroit Police Commissioner

1962-1963

The Old Guard administered the basic cordialities to their new boss but as Edwards began to probe irregularities in police conduct, the resistance tightened. The two sides would be at loggerheads for the duration. Since the Old Guard would not budge, Edwards attempted to break up the senior leadership, but they would not go easily. From the onset, Edwards went into his new job anticipating major changes.

Knowing the terrible friction this was bound to cause he vowed he would only head the department for two years so as not to hinder Cavanagh at election time. Edwards would not last two years though. The row he created throughout the department was so intense, he was forced to leave before the police department suffered a total meltdown.

Jerome Cavanagh and George Edwards

Internal Combustion

If George Edwards expected a showdown between his liberal ideologies and the Old Guard’s dictums, it was not long in coming. In January of 1962, a black Detroiter named Willie Daniels was reported to have threatened a woman with his gun over a $20 debt. When the police arrived at the Daniels home, his wife said he was not there. The police found him hiding in the basement, handcuffed him and, unable to locate the gun, began a physical interrogation.

Two days later Edwards learned of the beating from an informant and recognized an opportunity to turn a negative into a positive. Edwards quite simply was not going to put up with rogue police officers who habitually beat up minorities for the sport of it. While the Berg’s frowned on such things, the policeman’s code of “We take care of our own” generally took precedent. Until now.

Two days later Edwards learned of the beating from an informant and recognized an opportunity to turn a negative into a positive. Edwards quite simply was not going to put up with rogue police officers who habitually beat up minorities for the sport of it. While the Berg’s frowned on such things, the policeman’s code of “We take care of our own” generally took precedent. Until now.

Edwards ordered a police trial board to convene which included himself, Superintendent Louis Berg and Chief of Detectives Walter Wyrod. Edwards’ interrogation of the four officers in question revealed a host of contradictions. Even Wyrod was bewildered by the choppy testimonies. The city prosecutor was so ineffective Edwards believed he was in league with the police. The blue curtain of silence could not sufficiently explain away the extent of Daniels injuries, however.

Edwards ordered a police trial board to convene which included himself, Superintendent Louis Berg and Chief of Detectives Walter Wyrod. Edwards’ interrogation of the four officers in question revealed a host of contradictions. Even Wyrod was bewildered by the choppy testimonies. The city prosecutor was so ineffective Edwards believed he was in league with the police. The blue curtain of silence could not sufficiently explain away the extent of Daniels injuries, however.

Later that day, Berg and Wyrod tried to cajole Edwards into an acquittal, citing that any contradictions in evidence should be ruled in favor of the police. Edwards in turn demanded a guilty verdict. Wyrod strenuously voiced his objections. “Boss, we can’t do that. If I voted these men guilty, my own men would never work for me again.”

Later that day, Berg and Wyrod tried to cajole Edwards into an acquittal, citing that any contradictions in evidence should be ruled in favor of the police. Edwards in turn demanded a guilty verdict. Wyrod strenuously voiced his objections. “Boss, we can’t do that. If I voted these men guilty, my own men would never work for me again.”

It was a 2-1 vote for acquittal, Edwards being the lone dissenter. Edwards had lost this battle but the war would rage on. In the months to come the animosity would grow as the Old Guard would do their utmost to push the pesky commissioner out of office. Edwards believed a deliberate slowdown in arrests was enacted to give the public impression his liberal programs were ineffective. Police were hesitant to make arrests because Edwards’s liberal policies put them at risk for reprisal or dismissal by using Old Guard methods. Their beliefs were buttressed by the pessimistic views of well known Los Angeles police Chief William Parker, the anti-thesis of Edwards:

It was a 2-1 vote for acquittal, Edwards being the lone dissenter. Edwards had lost this battle but the war would rage on. In the months to come the animosity would grow as the Old Guard would do their utmost to push the pesky commissioner out of office. Edwards believed a deliberate slowdown in arrests was enacted to give the public impression his liberal programs were ineffective. Police were hesitant to make arrests because Edwards’s liberal policies put them at risk for reprisal or dismissal by using Old Guard methods. Their beliefs were buttressed by the pessimistic views of well known Los Angeles police Chief William Parker, the anti-thesis of Edwards:

Changing of the Guard

Perhaps the last blizzard in the Cold War between the Old Guard and Edwards occurred in August of 1962 when the Detroit Police Department held its 36th annual Field Day exercises at Tiger Stadium before 35,000 enthusiastic Detroiters. Edwards driver was told the event started at 2:00 when in reality it started at 1:30. Edwards was certain this misinformation was intentional, knowing how foolish he would look showing up late. Edwards showed up unabashed and cheered on the DPD in a tug-of-war against Toronto’s finest but this was the final insult.

While the police commissioner was not endowed with the power to hire or fire police personnel, he did have the power to transfer officers. Edwards informed Louis Berg that he was transferring the brothers to the traffic division, a clear demotion. The loss of face was too much for the Bergs and they opted into early retirement. Their surprised resignation shattered department morale and further enhanced the bull’s-eye on Edwards. The Bergs were the ideological skeleton which held the Old Guard up and the old school constitution they had written was quickly being torn to shreds. Edwards had won the biggest fight of his life, but at what price?

While the police commissioner was not endowed with the power to hire or fire police personnel, he did have the power to transfer officers. Edwards informed Louis Berg that he was transferring the brothers to the traffic division, a clear demotion. The loss of face was too much for the Bergs and they opted into early retirement. Their surprised resignation shattered department morale and further enhanced the bull’s-eye on Edwards. The Bergs were the ideological skeleton which held the Old Guard up and the old school constitution they had written was quickly being torn to shreds. Edwards had won the biggest fight of his life, but at what price?

With the departure of the Berg brothers, the police department began to spin out of control. Edwards became a marked man. His top commanders were against him, Detroiters who voted for Cobo in 1949 still disliked Edwards and there were persistent rumors that Cavanagh himself had had enough of the grumbling.

With the departure of the Berg brothers, the police department began to spin out of control. Edwards became a marked man. His top commanders were against him, Detroiters who voted for Cobo in 1949 still disliked Edwards and there were persistent rumors that Cavanagh himself had had enough of the grumbling.

Word was out on the street that beat cops weren’t doing their jobs. Constantly being under Edwards’s microscope, many cops were hesitant to make sensitive arrests for fear of reprisal by the commissioner. Morale was at rock bottom. In early 1963 two white Detroit police officers were shot to death in less than a month by black civilians. Edwards “soft stance” on crime was blamed. In July, a well-known black prostitute was shot and killed by a white police officer after she slashed him with a knife. Edwards reviewed the case and announced the officer acted properly. Edwards was being vilified in black and white circles. Rumors swirled that Edwards was secretly seeking an out in the form of a federal judgeship. Whether Edwards felt his mission was accomplished or the walls were closing in on him, we will never know. In December of 1963 George Edwards traded in his shield for a gavel as President Kennedy nominated him for a circuit court position. Perhaps this was a dignified out for a stubborn man who would not say uncle but it could not have come at a more convenient time for the Detroit Police Department was on the verge of a meltdown.

Word was out on the street that beat cops weren’t doing their jobs. Constantly being under Edwards’s microscope, many cops were hesitant to make sensitive arrests for fear of reprisal by the commissioner. Morale was at rock bottom. In early 1963 two white Detroit police officers were shot to death in less than a month by black civilians. Edwards “soft stance” on crime was blamed. In July, a well-known black prostitute was shot and killed by a white police officer after she slashed him with a knife. Edwards reviewed the case and announced the officer acted properly. Edwards was being vilified in black and white circles. Rumors swirled that Edwards was secretly seeking an out in the form of a federal judgeship. Whether Edwards felt his mission was accomplished or the walls were closing in on him, we will never know. In December of 1963 George Edwards traded in his shield for a gavel as President Kennedy nominated him for a circuit court position. Perhaps this was a dignified out for a stubborn man who would not say uncle but it could not have come at a more convenient time for the Detroit Police Department was on the verge of a meltdown.

Detroit was not ready for George Edwards in 1949. Nor was it ready for him in 1962. He was an idealist whose time had not yet come and when it did he was out of position to guide Detroit. Edwards was great in the short term to tackle difficult social issues and attempt to set things straight, but in the long run he was causing more havoc to the police department than Detroit’s criminals. He was simply too much, too soon. If George Edwards could not bring change to society, then society would force change any way it could.

Detroit was not ready for George Edwards in 1949. Nor was it ready for him in 1962. He was an idealist whose time had not yet come and when it did he was out of position to guide Detroit. Edwards was great in the short term to tackle difficult social issues and attempt to set things straight, but in the long run he was causing more havoc to the police department than Detroit’s criminals. He was simply too much, too soon. If George Edwards could not bring change to society, then society would force change any way it could.

Old Wine in New Bottles

By 1967 there were only a few officers left in the Detroit Police Department who were holdovers from the 1943 riot. One of them was Deputy Superintendent John Nichols, the number two man in the department.

A former army lieutenant colonel in World War II, Nichols was the old sage on the force, the hardnose, go to man who knew how the departmental wheels turned. He had seen it all in his twenty-five years on the force, including the surreal life on the infamous 12th Street:

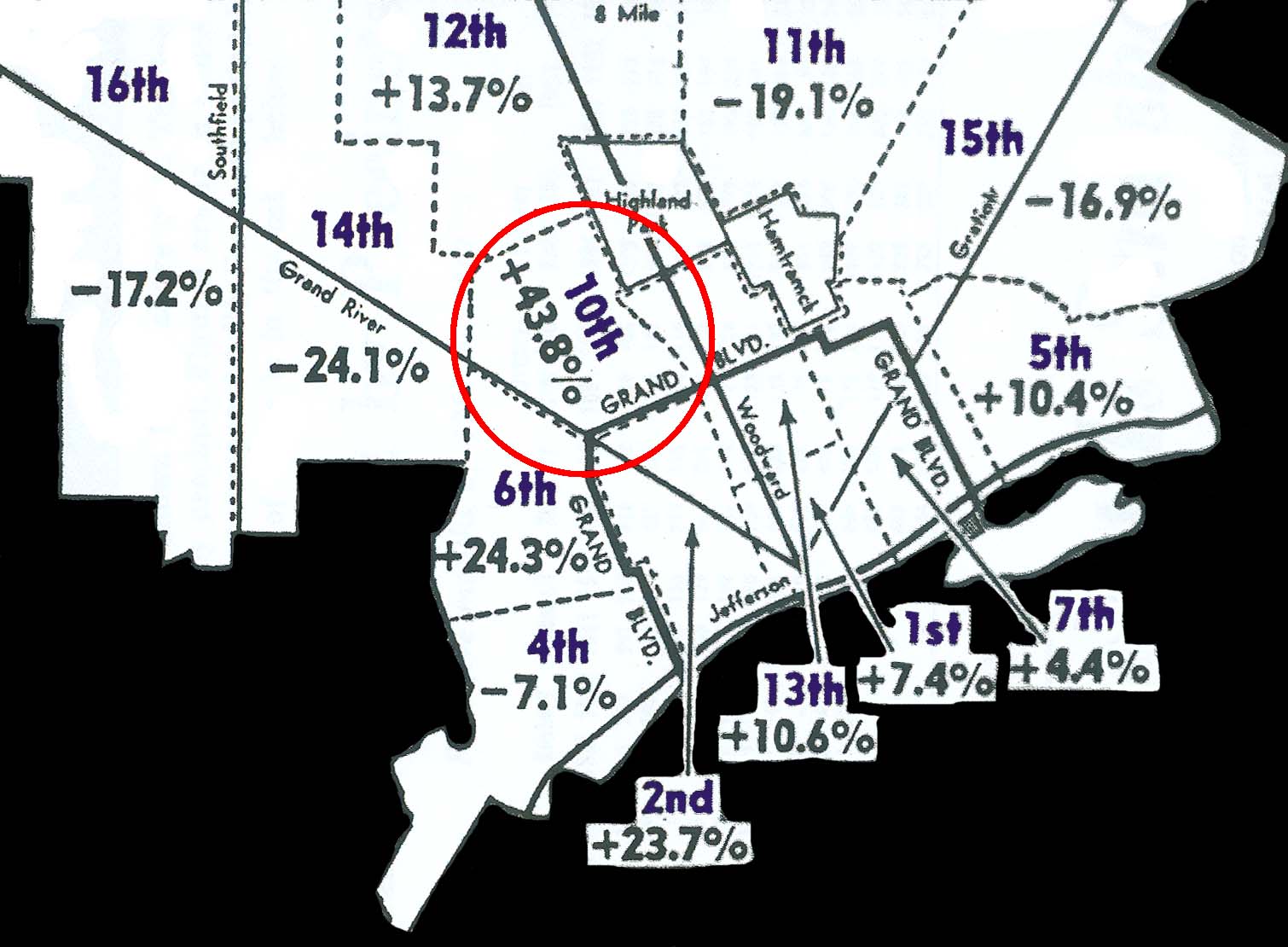

"When you work in a precinct like that (10th) I think you get a different savor than somebody from the outside. I’ve been down there (12th Street) on Saturday nights when I was working detective at the time and an outside department lieutenant was on a Ride Along Program, and he’d be terrified. And to me it was just an ordinary Saturday night. People lived on the street, people drank on the street, people conducted business on the street because the houses and the apartments were overcrowded and that was where they lived and once you had adapted to that, you didn’t see that seething mass of humanity that somebody from the outside did."

John Nichols

John Nichols

Deputy Superintendent - 1967

Detroit Police Department

Eugene Reuter

Eugene Reuter

Superintendent 1963-1967

Detroit Police Department

Reuter was another of the old school line of DPD commanders. Reuter joined the department in 1929 and pounded the beat for years, learning the job the hard way. He was no stranger to hard work, having work in the coal mines and on the line at Hudson Motors before joining the force. It was Reuter whom George Edwards tapped to take over after the sudden departure of the Berg brothers.

Reuter was regarded as tough but fair, a cop's cop. He once demoted a scout car officer onto a beat because he spotted him puffing a cigar "like a millionaire" as Reuter put it. Reuter made it eminently clear he would not be "a yes man to the commissioner. If I don't agree, I'll tell him so. He can go over my head to set the policy if he wants to, but if I'm right or I think I'm right, the boss is gonna know about it."

Reuter was regarded as tough but fair, a cop's cop. He once demoted a scout car officer onto a beat because he spotted him puffing a cigar "like a millionaire" as Reuter put it. Reuter made it eminently clear he would not be "a yes man to the commissioner. If I don't agree, I'll tell him so. He can go over my head to set the policy if he wants to, but if I'm right or I think I'm right, the boss is gonna know about it."

A 1963 map of the Detroit Police precincts - note the encircled 10th (a.k.a. The Bloody Tenth) precinct, the epicenter of the riot, and the percent increase in crime from the year before, a portent of things to come.

Detroit Police Commissioner

1963 - 1968

Ray Girardin was the personification of old Detroit. Born in the shadow of Most Holy Trinity Church in Corktown, his vast array of personal experiences made him an excellent choice to lead the Detroit Police Department through the turbulence of the 1960s. Girardin had spent thirty years as a crime reporter for the defunct Detroit Times. As such, he knew the streets, the criminal element and how it functioned. He also understood the trials and tribulations of the average beat cop, often riding around with them in the midnight hours in an attempt to drive that point home.

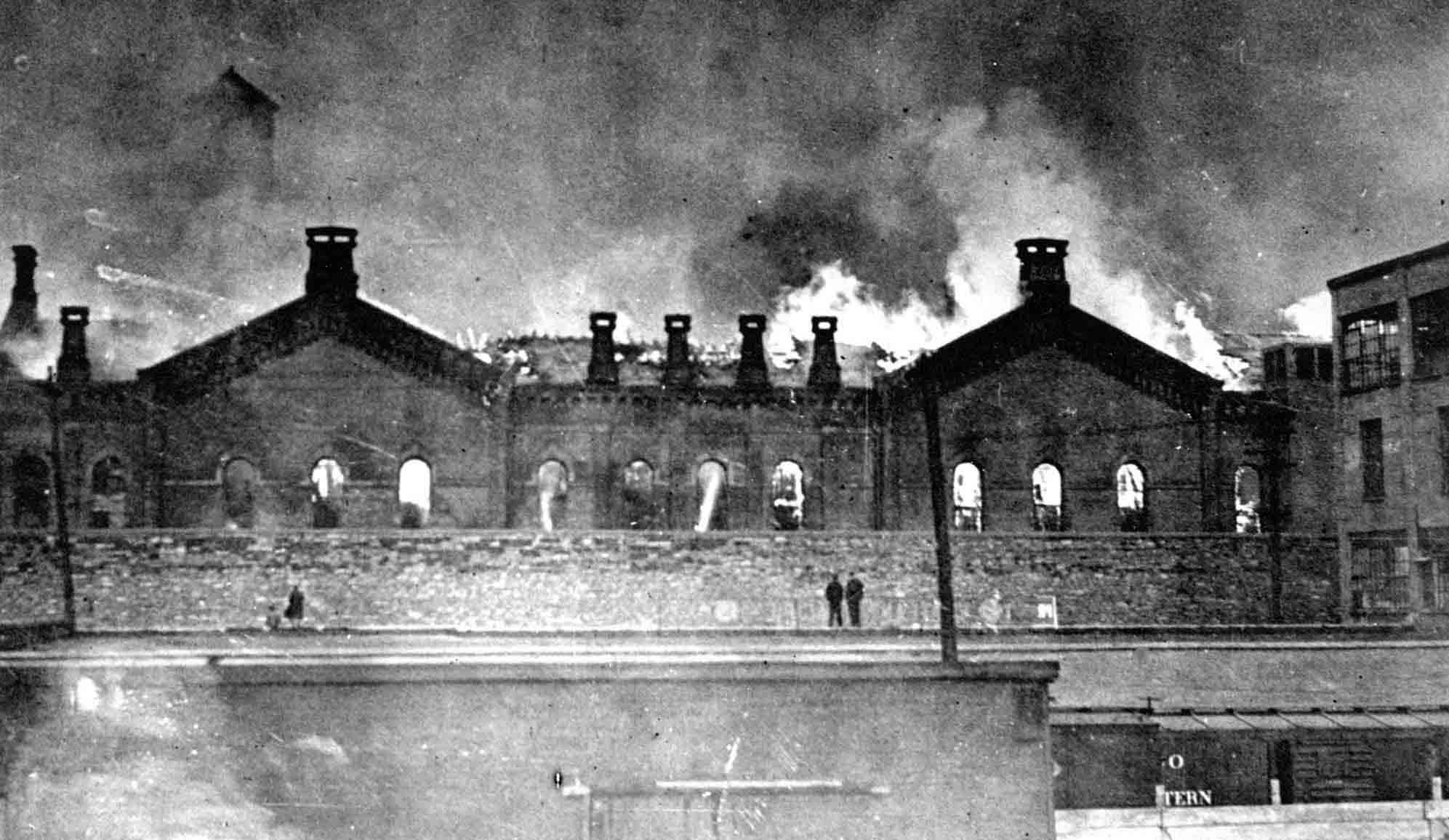

It has been said that everyone’s life revolves around one or two key events. For Girardin, that came his rookie year as a crime reporter when he was sent to cover a prison riot at the old Ohio State Penitentiary in Columbus. A fire of mysterious origin had started and 342 inmates died a gruesome death because the guards either couldn’t or wouldn’t open the cell doors. A riot ensued and Ray was the only reporter to get in and talk to the inmates who had taken over the prison. Ray built an immediate rapport with the prisoners, many of them hardened lifers, whose street sharp intuition told them Ray would not betray their confidences or skew their story. It was a characteristic that would define his entire life.

It has been said that everyone’s life revolves around one or two key events. For Girardin, that came his rookie year as a crime reporter when he was sent to cover a prison riot at the old Ohio State Penitentiary in Columbus. A fire of mysterious origin had started and 342 inmates died a gruesome death because the guards either couldn’t or wouldn’t open the cell doors. A riot ensued and Ray was the only reporter to get in and talk to the inmates who had taken over the prison. Ray built an immediate rapport with the prisoners, many of them hardened lifers, whose street sharp intuition told them Ray would not betray their confidences or skew their story. It was a characteristic that would define his entire life.

1930 Easter Sunday - The Ohio State Penitentiary goes up in flames costing 342 inmates their lives and a young rookie reporter named Ray Girardin his innocence. Girardin was stunned by the macabre scene. Dead prisoners still locked in their cells with their heads buried in toilets in a vain attempt to avoid the deadly heat and smoke that hopelessly engulfed them. It was to emblazon the young reporter with a new perspective on civil rights for all sectors of society.

Below: Mass funeral for inmates.

Taking the reins of the Detroit Police Department, Girardin knew of the volatile atmosphere that hovered over the city when he took over in 1963 and he immediately sought to alleviate potential eruptions:

The dreaded Motor Traffic Bureau Commandos of the Detroit Police Department, seen here drilling on Belle Isle, were the Detroit Police Departments final answer to riot control. By the time they made an appearance on the scene it could be widely assumed that any hope of a genteel or rational solution to quell the disturbance had long since been exhausted and more provocative methods would now be employed. Girardin was specifically brought in as commissioner to impart his common sense and humanity on what was widely known to be an overly aggressive police department.

A few years into his retirement, Ray Girardin reminisced about his first days as commissioner. “The Commandos were formed after the 1943 race riot, and were similar to the old police flyer, a car that used to be sent out to trouble with six cops who would just break every head in sight, no matter if it was a passerby or old ladies. Well, the Commandos were twelve or fourteen of the biggest men in the stationary traffic division (you had to be very tall for that assignment). But of course when I took over the police department they were all pushing sixty.”

Girardin later inquired, “Where do we keep our weaponry? I was told it was in the municipal garage. I wanted to see it, so we went over. There were heavy clubs – if you hit someone with one, you’d have killed him if you hit him in the ankle.” When Girardin asked to see the department plans to contain a riot he was told, “What riot plans? We’ve got the Commandos!”

Girardin on the 1967 riot:

"It wasn’t a race riot in the sense that blacks and whites were fighting each other,

"It wasn’t a race riot in the sense that blacks and whites were fighting each other,

as in 1943. This was a revolution by black people over, I think, the system. I saw

as in 1943. This was a revolution by black people over, I think, the system. I saw

the same expressions on the faces of some of the looters hurrying away with an

the same expressions on the faces of some of the looters hurrying away with an

armful of stuff they probably couldn’t even use that I had seen on the faces of

armful of stuff they probably couldn’t even use that I had seen on the faces of

convicts in prison riots I had covered. It was a wild, glazed look. I suppose it’s what

convicts in prison riots I had covered. It was a wild, glazed look. I suppose it’s what

is meant by “going berserk”. In prison riots they looted and took things they didn’t

is meant by “going berserk”. In prison riots they looted and took things they didn’t

want and burned and destroyed things that were meaningful to them – their gymnasium,

want and burned and destroyed things that were meaningful to them – their gymnasium,

the library, the auditorium. And so maybe there’s an analogy between prisoners in a

the library, the auditorium. And so maybe there’s an analogy between prisoners in a

prison and prisoners in a ghetto."

prison and prisoners in a ghetto."

As to why the controversial "no-shoot" order was given:

"Well, my position very simply was that I didn’t want to commit murder. And I

"Well, my position very simply was that I didn’t want to commit murder. And I

don’t think if you kill a person, under circumstances like that, because he’s

don’t think if you kill a person, under circumstances like that, because he’s

stealing a pair of shoes that don’t fit him or a television – they can be replaced,

stealing a pair of shoes that don’t fit him or a television – they can be replaced,

but you know, life can’t."

but you know, life can’t."

"We stopped this business of the police beating up people because they were black,

and I say we stopped it because we were firing policemen that did it. And that had

a hell of an effect. It was not uncommon, if a person, particularly a black, walked into

a police station and complained about a policeman that he’d get the piss kicked out

of him and get locked up."

"I look back over almost thirty-five years in the police service, thirty-five years of

dealing with the worst that humanity has to offer. I meet the failures of humanity daily,

and I meet them in the worst possible context. It is hard to keep an objective viewpoint.

But it is also hard for me to believe that our society can continue to violate all the fundamental

rules of human conduct and expect to survive. I think I have to conclude that this civilization

will destroy itself, as others have before it. That leaves, then, only one question – When? "

Ray Girardin - A Charitable Life

and what it wants enforced as law. "

and what it wants enforced as law. "